Drilling for Natural Gas in the World’s Longest Art Gallery

~ Valerie Monsey

Mark and I had been looking forward to our visit to Nine Mile Canyon in central Utah in the summer of 2006. We have been visiting Utah's remote and beautiful canyon country regularly since falling in love with this part of the world many, many years ago. Our favorite activity is hiking in the canyons, where the solitude and stunning natural beauty provide a much needed respite from living and working in Seattle. The trip to Nine Mile Canyon was to include one of our favorite activities, searching for rock art sites.

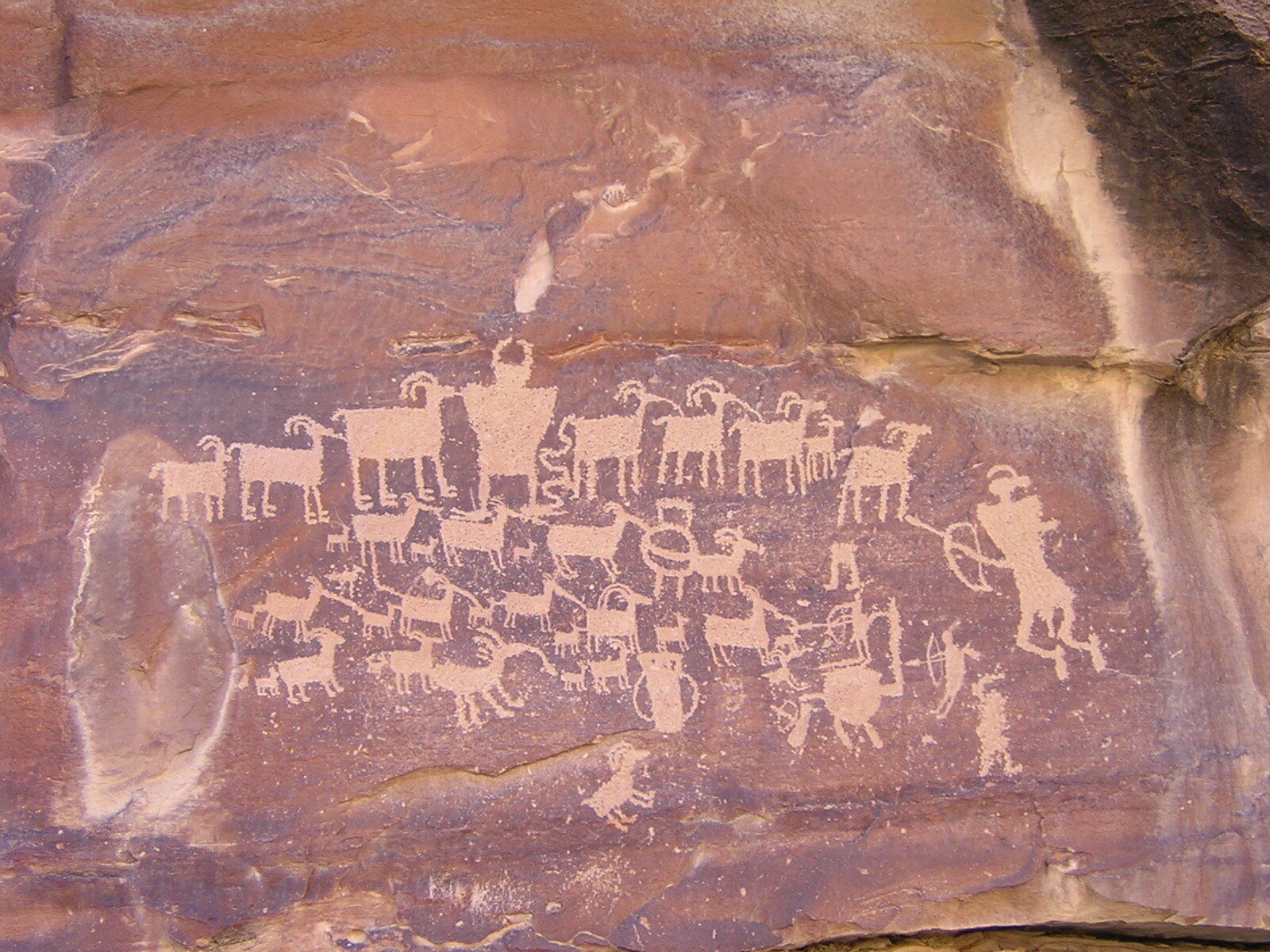

Nine Mile Canyon, which is actually 40 miles long, is often called the “world's longest art gallery”, and is supposed to contain over 10,000 petroglyphs, pictographs, and prehistoric archaeological sites. It is thought that the Archaic people lived in the canyon 8000 years ago, the Fremont people about 2500 years ago, and more recently the Ute people made it their home. A road through the canyon was constructed in the late 1880's, and historic sites including the ghost town of Harper remain.

We have visited Utah many times, and are well versed in how to “visit with respect”, including not touching any rock art (petroglyphs and pictographs), and not disturbing any archaeological sites that you come across. Some of these sites could be a thousand years old, and we like to think that maybe a thousand years from now people will still be able to experience the wonder of stumbling onto rock art sites and ancient ruins while exploring remote canyons.

Our plan was to spend an enjoyable day driving slowly up the narrow, winding, gravel road, binoculars and guide book in hand, searching for rock art and ancient granaries in the canyon walls. We planned to set up our tent and camp on public land outside of the canyon area, and then spend a second day exploring.

What we didn't know at the time was that the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM), who manages most of the land in the canyon, had recently granted drilling rights in the West Tavaputs Plateau to the Bill Barrett Corporation (BBC), and that Nine Mile Canyon was now a primary access route for this major industrial operation, with a plan to drill up to 800 gas wells.

It didn't take long for us to realize our mistake. Speed limit signs in the canyon posted by BBC made it clear that this special place that contemporary tribes value as a place of spiritual heritage was now an industrial zone. A sign targeting BBC personnel and contractors stated that the speed limit was 20 mph and 10 mph on corners due to heavy truck traffic, and "VIOLATORS WILL BE TERMINATED".

Our next clue was the tanker trucks. A convoy of tanker trucks worked it's way down from a side road ahead of us, filling the canyon with dust. We speculated on what they could be for. Maybe they were water trucks being used to spray the road to keep the dust down? Small sections of road were wet, but it did nothing to stop the clouds of fine dust from filling the air. We were not impressed.

We drove past a large industrial building located on the far side of the canyon. Loud, booming sounds emanated from the building. We had no idea what it was, but figured it was something to do with the drilling operations. It was definitely not peaceful.

Next were the contractors in their pickup trucks. There were many blind corners on this gravel road, and it soon became clear that the contractors did not expect to see traffic. We avoided a head-on collision by stopping before a blind corner as we could hear a truck coming. The truck came racing around the corner, saw us, and slammed on the brakes, skidding to a stop in the gravel. We learned to stop and pull over when we heard a vehicle coming. Our expectation of a peaceful day exploring the canyon turned into a white knuckled driving experience as it was clear it was up to us to avoid a collision. No one was even close to following the posted speed limits.

Next was the tanker truck upside down in a creek that was right next to the road. Another truck was stopped there, but we didn't know what the driver was doing and he wasn't interested in talking to us. We took a closer look after the second truck left. The truck in the creek was coated in dust. How long had it been there? How could it happen? Were vehicle fluids getting into the creek, the only water source for miles around?

Finally we came across several large tanks next to the creek. Diesel from the generator had spilled onto the ground with no effort to clean it up. Abandoned vehicle batteries lay dumped on the ground. There were no spill cleanup materials anywhere around.

The dangerous driving conditions made us abandon our trip early. We just wanted to get out of there. It was so disappointing to see how this amazing place was being treated. I always remember that trip when I hear about proposed oil and gas drilling operations, and how oil and gas companies say they can be good stewards of the environment. I'm not opposed to all drilling. My house is heated with natural gas. But what was happening in Nine Mile Canyon was wrong.

When I decided to write this post, I did some online research to see how Nine Mile Canyon has been doing since that trip. I learned that this area has been the subject of countless appeals and lawsuits regarding the potential impacts from proposed oil and gas drilling in the area.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation included Nine Mile Canyon on it's list of "America's Most Endangered Places" in 2004. An archeologist at the local Bureau of Land Management office who voiced concern over the potential significant impacts to the canyon's rock art was barred from conducting any oversight of the project. Online newsletters posted by the Nine Mile Canyon Coalition, a nonprofit group created in the 1990's advocating for the preservation and protection of the canyon, document thousands of hours of effort in working with the BLM towards this goal.

The conditions we observed on our trip apparently continued to get worse, and by 2008 the lawsuits were continuing. A scientist documented that magnesium chloride, which was being used as a dust suppressant, was coating rock art sites.

The Nine Mile Canyon Coalition noted in a 2010 newsletter that what the BBC called "minor seepage" was an ongoing leak from a compressor that had been going on for at least a year. The spill was discovered when a truck driver noticed a sheen on Nine Mile Creek. I learned that there was an explosion and fire at the Dry Canyon natural gas compressor facility in 2012, which I think is the noisy building we observed in 2006.

Finally a formal agreement was made in 2010 that was a compromise between a coalition of conservation groups, including SUWA, and state and local agencies. This document requires that the BBC conduct extensive mitigation and restoration work, and reduced the overall scope of the development. The road through the canyon was paved in 2013. I found a letter prepared by The Nine Mile Canyon Coalition in 2016 protesting an oil and gas lease sale. The August 2020 Newsletter notes that "the coalition and several partners protested and requested a review of a particularly bad BLM decision on gas drilling that would have had major impacts on Nine Mile Canyon".

This research has made it even more clear to me how incredibly important the tireless efforts of volunteers and conservation groups are in protecting our public lands.

The battle to save Nine Mile Canyon continues.